We’re coming up on the end of Black History Month, and I have a story to tell you all about Styles Linton Hutchins. Trista here, and I’m diving headfirst into the first installment of BiblioChatt, where we collaborate with the Chattanooga Public Library to answer your questions about the city’s history. This month, y’all wanted to learn about S.L. Hutchins’ life, and after doing my research, I understand why.

Meet Styles Linton Hutchins

Styles Linton Hutchins was born on Nov. 21, 1852 in Lawrenceville, Georgia. I couldn’t find any information about his mother, but his father was an artist, and a good one, too. He sent Styles to Atlanta University, and from there, he became a teacher before accepting a principal position at Knox Institute in Athens, GA in 1871.

“Under his supervision the school flourished [...] but this did not satisfy his restless, ambitious spirit,” –J. Bliss White, “1904 Biography and Achievements of the Colored Citizens of Chattanooga”

He resigned from Knox in 1873 and moved to South Carolina where he went to law school at the University of Columbia S.C.. He graduated in 1876 and served as a judge before the Supreme Court of S.C. until uncertainty of party policies and politics arose, leading him to resign.

From there, he went back to Georgia and demanded admission to the bar so he could practice law in his home state. However, the Georgia legislature passed an act requiring lawyers from other states to undergo an exam, and the allowance to practice was at the discretion of the presiding judge.

“To admit a negro upon social professional equality with white men was an innovation hardly to be tolerated.” –Judge Hillyer, the presiding judge at the time

I’m sure you guessed it — Hutchins put up a fight. He fought the legislature for six months before finally being admitted to the Georgia Bar. He was the first black man to be admitted. And he practiced in Georgia until 1881, when he moved to Chattanooga after becoming weary of Georgia customs.

In Chattanooga, he immediately began practicing law, but quickly — within a year — shifted into politics and organized + established a newspaper with other black citizens called The Independent Age. At the time (1882), it was the only newspaper owned + operated entirely by black men.

In 1886, Hutchins was nominated by the Republican Convention to run as a candidate for the TN legislature against Mr. Dunbar (I couldn’t find much information about him), who was one of the most popular Democrats in Hamilton County. I’m sure this will come as no shock — Hutchins won, even after the election was contested by the Democratic party.

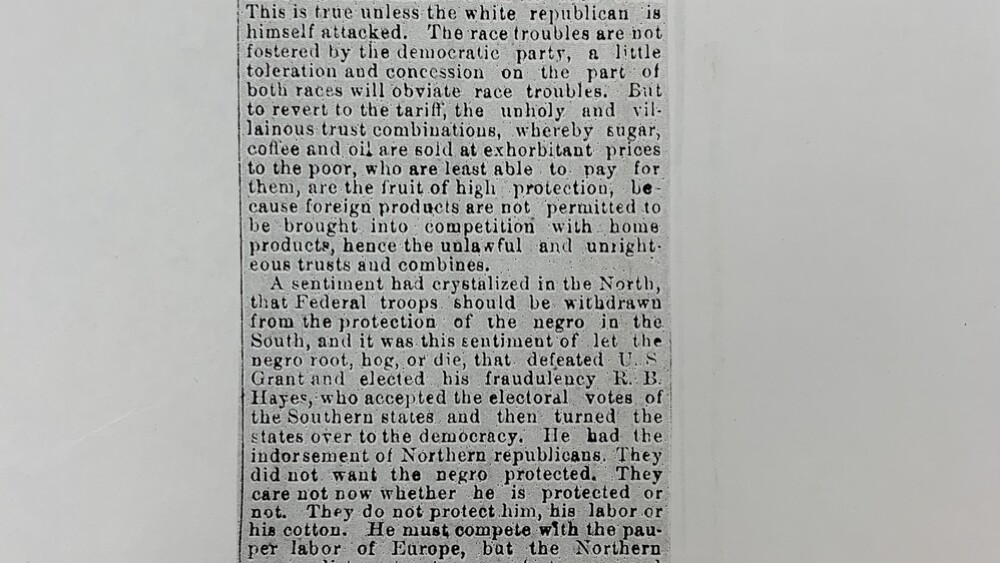

Within two years (I’m starting to see a pattern here), Hutchins realized his qualms with Republicanism and denounced it when he left office in 1888. Below is a newspaper clipping from the The Chattanooga Times (now the Chattanooga Times Free Press) of Hutchins’ thoughts on Republicanism.

“I believe in the memorable words of President Grover Cleveland, that to talk of free trade is irrelevant. The social disturbances between the races are not necessarily political.” –Styles L. Hutchins, The Chattanooga Times

Now, in order to tell the full story, I have to introduce Ed Johnson, of whom many of you have heard.

Meet Ed Johnson

On Jan. 27, 1906, Ed Johnson was accused of assaulting a teen from St. Elmo, Miss Nevada Taylor, the daughter of William Taylor, who was a naturalist + well-known throughout the city. You get the idea — this family was loved by Chattanooga, so an assault against Nevada stirred up quite a bit of anger.

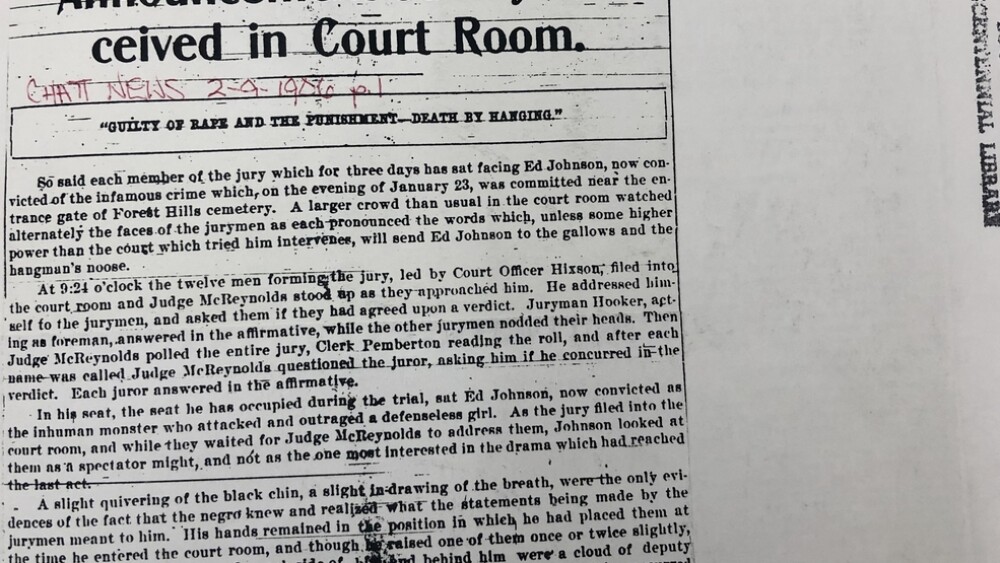

Because the crime took place at night, Nevada didn’t have a good description of her attacker. A few members of the jury had their doubts because of this, and the St. Elmo community was also unconvinced of Johnson’s role in the crime. He pleaded not guilty during his trial, but on Feb. 9, 1906, the jury ended up convicting him — the sentence was death by hanging.

The defense

Enter Styles Hutchins and his partner, Noah Parden. They were hired by Ed Johnson’s father, who was convinced of his son’s innocence. They claimed a writ of error concerning alleged mistakes in the trial, and the case was reopened before Tennessee’s Supreme Court.

“Reports from the supreme court on the procedure in the case are that Johnson’s attorneys alleged that their client had not had a fair trial as guaranteed by the constitution. The court dismissed the petition because there was a lack in the record of a bill of exceptions and nothing in the record showed that the lower court was asked to grant a new trial.” –The Chattanooga Times, March 5, 1906, p. 5

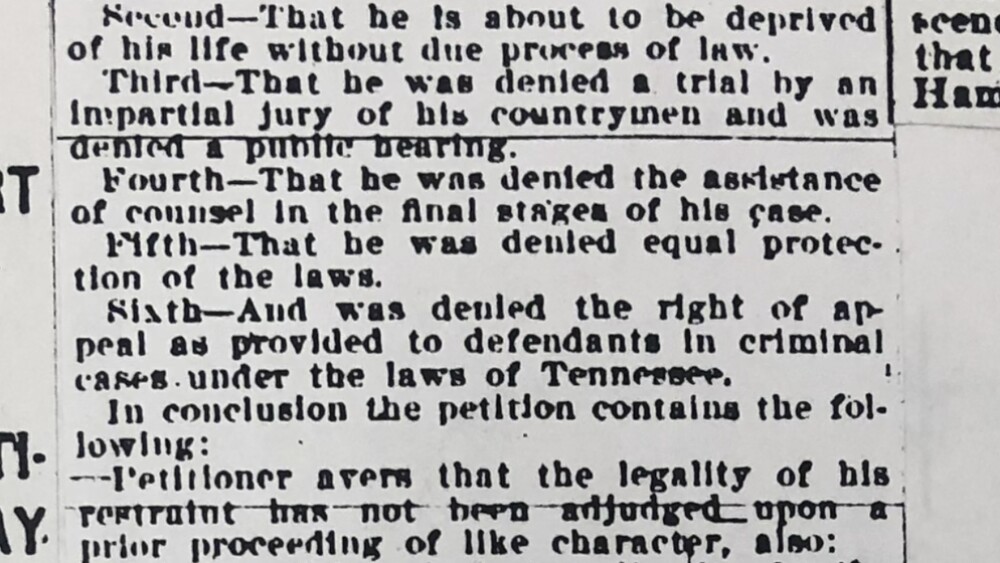

Hutchins + Parden were not about to give up the fight, though — they filed for writ of habeas corpus on March 8, 1906 and provided six charges in the petition.

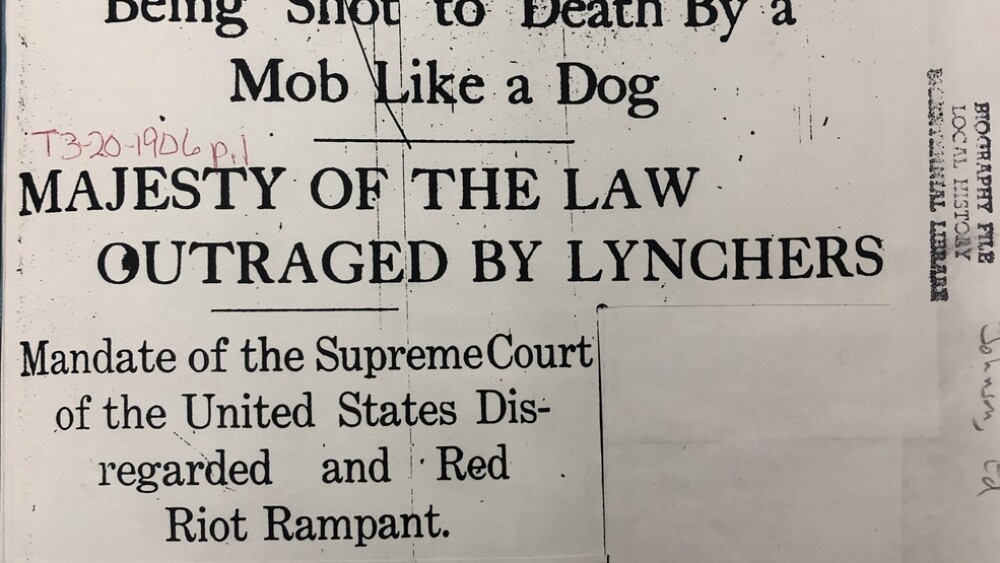

But still, it wasn’t enough. Writ for habeas corpus was denied, and Johnson was brought back to the Hamilton County jail to await his death. On March 14, 1906, in a last ditch effort, Hutchins + Parden decided to take the case to the United States Supreme Court (United States vs. Shipp) and arrived in D.C. on March 16. Johnson was granted appeal by the supreme court, but it would prove to be too late — on March 19, 1906 he was dragged out of his cell and killed by an angry mob on the Walnut Street Bridge.

I won’t go into the details of the lynching here aside from saying it was brutal. The headline below says plenty, and it’s another story for another time because the focus here is on Hutchins.

Post lynching

Hutchins + Parden had come so close to pulling through with a new trial for their client, but they were no match against the emotional response of Chattanooga citizens. And because of the emotions concerning Ed Johnson and his defense, Hutchins + Parden did not feel safe returning home.

“Neither man returned to Chattanooga. Friends and relatives sent the lawyers messages that if they did come home, they would most likely be killed by a mob instantly.” –Mark Curriden and LeRoy Phillips, JR., “Contempt of Court: The Turn of the Century Lynching that Launched a Hundred Years of Federalism,” p. 349

According to the book “Contempt of Court,” the two toured the North for a while and lectured on the events of the Johnson case before moving to Oklahoma. And that’s where I came to a dead end in my research. I assume it’s because Hutchins fled the area, so local media went radio silent on his life after the lynching of his client.

So, I cheated on this project a little (please forgive me) and found a good article for closure in the Star Courier out of Kewanee, Illinois. According to this, Hutchins became a barber in Kewanee. At first that came as a shock to me, considering his prolific skills as an attorney + politician, but upon reflection, I get it — the Johnson trial, and events surrounding it, was probably quite traumatizing for Hutchins, and becoming a barber in a new city sounds like a fine life to live after all of that.

Hutchins passed away in 1950 — he was nearly 98 years old.

Present day

Last year, Mayor Andy Berke’s office launched a Styles L. Hutchins Talent Retention Fellowship in honor of Hutchins and his place in Chattanooga’s history. We recently posted about the current members of the fellowship here. The goal of the fellowship is to foster inclusion and keep diverse talent in our city. We enjoyed this article from the Chattanooga Chamber’s Business Trend on the current Styles L. Hutchins fellows.

There’s also an Ed Johnson Memorial scholarship founded in his memory. It was established in 2009 and is awarded to a student pursuing a career in criminal justice. This is a copy of the 2018 scholarship application.

Chattanooga State Community College put on a play about the life and trial of Ed Johnson in 2018 called “Dead Innocent-The Ed Johnson Story.” At this time, I’m unsure if it will hit the stage again, but I know I’d buy a ticket to see it.

And, believe it or not, on Feb., 26 of this year congress made lynching a federal crime. Raise your hand if you, like me, thought it already was a crime. ✋ According to NBC News, Congress has failed nearly 200 times to make lynching a crime. This bill comes 65 years after the infamous lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till.

Quote-worthy

“[Hutchins and Parden] risked their careers, their place in society, their homes, even their lives, to protect the rights of one young black man they did not know. Yet there is no statue in Chattanooga honoring Parden or Hutchins, no memorial to their contribution to civil rights. Their names are not taught in schools. Despite their marvelous achievements, they have been forgotten by history. If Sheriff Shipp has a statue in his honor that stands to this day, isn’t it time to recognize Noah Parden and Styles Hutchins?”

–Mark Curriden and LeRoy Phillips, JR., “Contempt of Court: The Turn of the Century Lynching that Launched a Hundred Years of Federalism,” p. 349

FYI — there is currently an ongoing effort to honor Ed Johnson, Styles Hutchins + Noah Parden by the Ed Johnson Project. In 2019, Hamilton County Commission approved $100,000 in funding for this project, and a memorial to Johnson is in the works — it’s supposed to be completed later this year. You can read more about the memorial here.

Footnote

All materials used, with the exception of the Star Courier article, can be found in the local history department at the downtown branch of the Chattanooga Public Library. (Sheldon Owens was a huge help — thank you, Sheldon. 🙏) I merely got to skim this story, and I highly recommend diving in yourself as it’s an important piece of Chattanooga’s history.